Sometimes you have to go through Hell to get to Heaven. In the case of Lionel Aldridge, he took the reverse path.

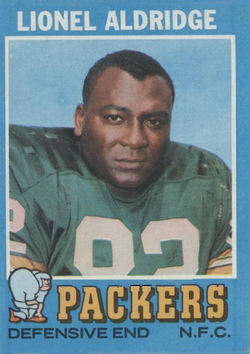

Aldridge was born on February 14, 1941, in Evergreen, Louisiana, and was drafted by the Green Bay Packers in the Fourth Round of the 1963 draft after a standout college career at Utah State.

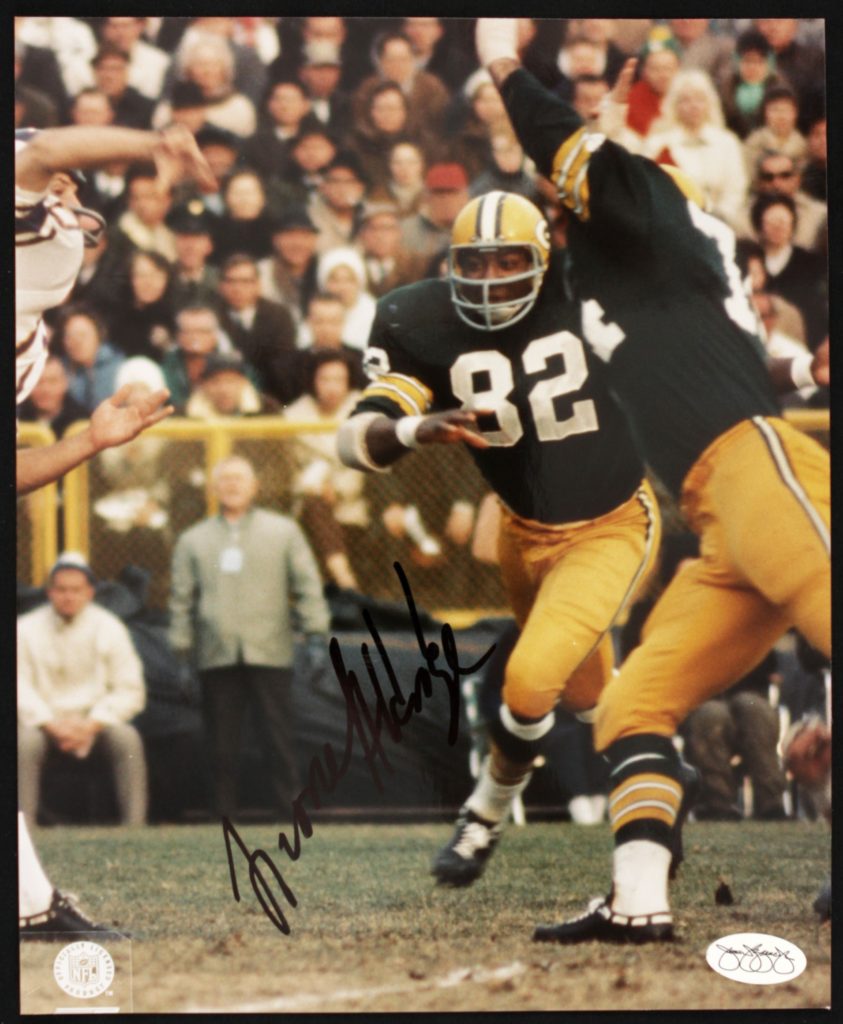

While Packers’ coach, Vince Lombardi, was always wary of starting rookies, Aldridge cracked the vaunted Green Bay lineup in his first professional year. He quickly became a cornerstone of the staunch and stingy defenses of the glorious 1960s playing right defensive end opposite fellow Louisiana native and future Pro Football Hall of Famer, Willie Davis.

Although the NFL didn’t log official stats for tackles during Aldridge’s era, he was renowned throughout the league as a solid tackler that helped anchor that stout Packers’ defensive line.

As a Packer, he played prominent roles in three straight NFL Championships with wins over Cleveland in 1965, and Dallas both in 1966 and ’67. Perhaps it was that 23-12 victory in the 1965 title game that epitomized the smothering Green Bay defense of that era, as the Packers held Browns’ legendary running back, Jim Brown, to just 50 yards rushing in what would be the future NFL Hall of Famer’s final game.

Aldridge continued contributing to the team’s historical run of championships, helping Green Bay to victories in Super Bowl I (a 35-10 dismantling of the Kansas City Chiefs) and Super Bowl II (a 33-14 shellacking of the Oakland Raiders).

Aldridge enjoyed an 11-year pro career with his first nine seasons played in Green Bay and his final two as a Charger in San Diego. The six-foot-three, 255-pound beast was named an All-Pro in 1964 and was inducted into the Packers Hall of Fame in 1988.

Still, even with a physical shell as imposing as Aldridge’s could not protect life’s most fragile wonder: the brain.

After retiring in 1973, he turned to broadcasting. He became an analyst for the Packers and then for NBC. He even worked Super Bowl VII for the network following the 1973 season.

Things were seemingly going as well off the field as they had on.

But then, something changed. Something suddenly didn’t seem right.

His longtime friend Jim Irwin, who had broadcast Packers games for 29 years before retiring after the 1998 season, told the New York Times, “Lionel was a terrific success story that had some holes in it. He was a big, friendly teddy bear,” who experienced mood swings as a player. “He’d be ‘up’ one day and then the next day he’d snap at everybody.”

Irwin recounted an instance after Aldridge retired and was doing the color commentary on a Packers’ broadcast. “I asked him the first question of the day, and he stared straight ahead,” Irwin recalled. “He never took his eyes off the 50-yard line for the next three and a half hours and never said another word.”

Unbeknownst to Aldridge, his family or his friends, the former defensive superstar for the Packers was experiencing the beginning phases of paranoid schizophrenia.

The Mayo Clinic describes paranoid schizophrenia (PS) as a chronic mental illness in which a person loses touch with reality.

The most prominent PS symptom is auditory hallucinations or “hearing voices” along with severe delusional behavior, the fear of persecution and sensing usually irrational things that others don’t. There is no specific cause as to what triggers PS in adults, but both genetics and environment likely play roles. (Football and its head-on collisions have never been blamed on Aldridge’s PS.)

PS symptoms are more common and severe primarily because they attack a person in the later years of life, usually after the age of 30.

Aldridge was barely into his mid-30s when the episodes began. By the early 1970s, he began to hallucinate. Then, the voices started echoing through his brain.

On the website Guideposts (www.guideposts.org) Aldridge wrote frankly and frighteningly of his illness.

***

One of the most frightening signs that there was something seriously wrong with me was the voices I began hearing in 1974.

At first, they were just stray, nagging worries that dogged me through the day; self-doubts that we all have from time to time. They seemed to rise up out of nowhere—vague thoughts with an accusing edge, ‘You really don’t work very hard, do you?’

The voices were very scary and confusing. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want anyone to find out the terrible things happening inside my head. As an athlete, I’d been trained to be tough; it was not my nature to seek help. I wanted to be strong.

At first I tried to ignore them. But the voices grew more belittling and threatening; more real. I’d be standing in front of the mirror shaving when I’d hear from the next room, ‘You don’t take very good care of your family.’ “That’s bull!” I’d shout. I’d search the house for my tormentor. I’d mutter, as my wife, Viki, shook her head in dismay. There never was any intruder.

His marriage, which had produced two daughters, Michelle and Angela, collapsed. So did his job. Quickly the situation grew worse.

Aldridge chronicled the events on Guideposts.

Rumors flew around town that I was on drugs. That was completely false, but I was in no shape to prove otherwise. I was getting worse.

Soon that feeling of being watched wouldn’t let up, even on the air. Looking into the camera, I could barely hold my composure as I reported the nightly sports scores. The wide camera lens zooming in on me was a glistening, all-seeing eye that could plumb the farthest, most hidden reaches of my soul. Everyone who was watching on their TV sets, I was convinced, could see right inside my brain, where laid bare for all to look on in disgust were the grimmest secrets of my life.

I was sure there was a far-flung conspiracy to destroy me. I fought with total strangers on the street. I lost my job, (my family) and my friends. There was nothing left but the voices shouting in my head, as real to me as an opposing 260-pound pulling guard on a goal line stand back in my playing days.

My life spun out of control.

Aldridge was convinced by voices that he needed to leave his Milwaukee home.

He crisscrossed the country in an unruly wilderness of twisted interstates, sleeping in hotels and ultimately seedy flophouses. Once his savings were mostly exhausted, he started living in his car. In Florida, he ditched the car for a $100 and hit the streets with nothing more than a battered satchel on his shoulder.

Occasionally I hung around a town for a while doing odd jobs, living on the streets and eating at soup kitchens,” he wrote. “Quite naturally, people would stare at me, and that would only make my delusions of persecution worse. I never held a job for long…I’d become one of those lost, devastated souls. There were a lot of them out there with me, crippled by mental illness, but as I wandered the country I was only aware of my own haunted, unhappy world a million miles from the life I once had.

One night I slept in a field off an interstate near the Great Salt Lake. I didn’t notice when I woke u, but, while I was sleeping, my jewel-encrusted Super Bowl ring must have slipped off. Those rings are not easy to come by, and I’d hung on to mine as a kind of symbol of who I’d once been.

When I discovered the ring missing, it was as if I’d been stripped of one final link with my past. I sat in the middle of a sidewalk and wept into my hands.

‘Help me!’ I cried out. The sweat and tears streaked my dust-caked face. ‘Help! I’ll accept help from anyone.’

Turning to a well-worn Bible for guidance, he found the strength and courage to return to Milwaukee where, while still living on the streets, he was brought back into contact with old friends. He was, not without difficulty, committed to a hospital where he was diagnosed with PS.

“Slowly the doctors hit upon some drugs that helped,” he rejoiced. “Little by little my condition improved, and the voices gradually subsided. At first it was horrifying. It was an awful thing to face, like seeing a crazy man on the street and suddenly realizing that you are looking into a mirror.”

Although there is no cure for PS, Aldridge was able to recover and learn to live with the debilitating disease.

“I did recover,” he admitted. “Not without setbacks and relapses, not without moments when I thought I could never again face life, but I did get well with the help of friends, doctors who found the right medication to help me and the voice of a loving God.”

He discovered new strategies to cope with the world, including turning the voices around and convincing himself that, instead of negative things, the voices were actually preaching positive attributes about him. “I figured, maybe they’re saying good things like, ‘Hey, there’s Lionel Aldridge. He used to play for the Packers and then he got sick. Look how good he’s doing now.’ ”

In time, the voices went away thanks to medication and his faith in God’s master plan. He began travelling the country speaking to groups about mental illness and recovery. “It’s vital,” he said, “for patients, families and even doctors to see someone who has actually made it back.”

In January 1985 – the 18th anniversary of the Packers’ first Super Bowl win – Lionel received yet another gift. A group of his old teammates had commissioned an exact replica of the Super Bowl victory ring that Aldridge had lost.

“I knew that day that I had returned,” he surmised. “Even when you think you’ve lost everything in your life, there is always hope of finding a way back, sometimes to an even better place.”

Aldridge passed away on February 12, 1998, in Shorewood, Wisconsin, of congestive heart failure at the age of 56.

After a meteoric rise to fame and glory, and then a whiplashing plummet into darkness and despair, this gentleman of the game and Packers’ legend can now, finally, rest in peace.